Charles Hodge describing and summarizing Pelagianism (pt 1)

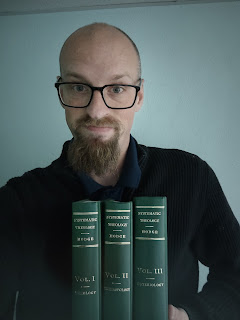

Today I was reading some of Charles Hodge's Systematic Theology and came across some great excerpts discussing Pelagianism. I've highlighted some particularly relevant sections that speak directly to beliefs held commonly among many contemporary western Christians.

|

| The quotes today are from Volume 2 of Hodges Systematic Theology set |

§ 4. Pelagian Theory

In the early part of the fifth century, Pelagius, Cœlestius, and Julian, introduced a new theory as to the nature of sin and the state of man since the fall, and of our relation to Adam. That their doctrine was an innovation is proved by the fact that it was universally rejected and condemned as soon as it was fully understood. They were all men of culture, ability, and exemplary character. Pelagius was a Briton, whether a native of Brittany or of what is now called Great Britain, is a matter of doubt. He was by profession a monk, although a layman. Cœlestius was a teacher and jurist; Julian an Italian bishop. The radical principle of the Pelagian theory is, that ability limits obligation. “If I ought, I can,” is the aphorism on which the whole system rests. Augustine’s celebrated prayer, “Da quod jubes, et jube quod vis,” was pronounced by Pelagius an absurdity, because it assumed that God can demand more than man render, and what man must receive as a gift. In opposition to this assumption he laid down the principle that man must have plenary ability to do and to be whatever can be righteously required of him. “Iterum quærendum est, peccatum voluntatis an necessitatis est? Si necessitatis est, peccatum non est; si voluntatis, vitari potest. Iterum quærendum est, utrumne debeat homo sine peccato esse? Procul dubio debet. Si debet potest; si non potest, ergo non debet. Et si non debet homo esse sine peccato, debet ergo cum peccato esse, et jam peccatum non erit, si illud deberi constiterit.”

The intimate conviction that men can be responsible for nothing which is not in their power, led, in the first place, to the Pelagian doctrine of the freedom of the will. It was not enough to constitute free agency that the agent should be self-determined, or that all his volitions should be determined by his own inward states. It was required that he should have power over those states. Liberty of the will, according to the Pelagians, is plenary power, at all times and at every moment, of choosing between good and evil, and of being either holy or unholy. Whatever does not thus fall within the imperative power of the will can have no moral character. “Omne bonum ac malum, quo vel laudabiles vel vituperabiles sumus, non nobiscum oritur, sed agitur a nobis: capaces enim utriusque rei, non pleni nascimur, et ut sine virtute, ita et sine vitio procreamur: atque ante actionem propriæ voluntatis, id solum in homine est, quod Deus condidit.” Again, “Volens namque Deus rationabilem creaturam voluntarii boni munere et liberi arbitrii potestate donare, utriusque partis possibilitatem homini inserendo proprium ejus fecit, esse quod velit; ut boni ac mali capax, naturaliter utrumque posset, et ad alterumque voluntatem deflecteret.”

2. Sin, therefore, consists only in the deliberate choice of evil. It presupposes knowledge of what is evil, as well as the full power of choosing or rejecting it. Of course it follows,—

3. That there can be no such thing as original sin, or inherent hereditary corruption. Men are born, as stated in the foregoing quotation, ut sine virtute, ita sine vitio. In other words men are born into the world since the fall in the same state in which Adam was created. Julian says: “Nihil est peccati in homine, si nihil est propriæ voluntatis, vel assensionis. Tu autem concedis nihil fuisse in parvulis propriæ voluntatis: non ego, sed ratio concludit; nihil igitur in eis esse peccati.” This was the point on which the Pelagians principally insisted, that it was contrary to the nature of sin that it should be transmitted or inherited. If nature was sinful, then God as the author of nature must be the author of sin. Julian therefore says: “Nemo naturaliter malus est; sed quicunque reus est, moribus, non exordiis accusatur.”

4. Consequently Adam’s sin injured only himself. This was one of the formal charges presented against the Pelagians in the Synod of Diospolis. Pelagius endeavored to answer it, by saying that the sin of Adam exerted the influence of a bad example, and in that sense, and to that degree, injured his posterity. But he denied that there is any causal relation between the sin of Adam and the sinfulness of his race, or that death is a penal evil. Adam would have died from the constitution of his nature, whether he had sinned or not; and his posterity, whether infant or adult, die from like necessity of nature. As Adam was in no sense the representative of his race, as they did not stand their probation in him, each man stands a probation for himself; and is justified or condemned solely on the ground of his own individual personal acts.

5. As men come into the world without the contamination of original sin, and as they have plenary power to do all that God requires, they may, and in many cases do, live without sin; or if at any time they transgress, they may turn unto God and perfectly obey all his commandments. Hence Pelagius taught that some men had no need for themselves to repeat the petition in the Lord’s prayer, “Forgive us our trespasses.” Before the Synod of Carthage one of the grounds on which he was charged with heresy was, that he taught, “et ante adventum Domini fuerunt homines impeccabiles, id est, sine peccato.”

6. Another consequence of his principles which Pelagius unavoidably drew was that men could be saved without the gospel. As free will in the sense of plenary ability, belongs essentially to man as much as reason, men whether Heathen, Jews, or Christians, may fully obey the law of God and attain eternal life. The only difference is that under the light of the Gospel, this perfect obedience is rendered more easy. One of his doctrines, therefore, was that “lex sic mittit ad regnum cœlorum, quomodo et evangelium.”

7. The Pelagian system denies the necessity of grace in the sense of the supernatural influence of the Holy Spirit. As the Scriptures, however, speak so fully and constantly of the grace of God as manifested and exercised in the salvation of men, Pelagius could not avoid acknowledging that fact. By grace, however, he understood everything which we derive from the goodness of God. Our natural faculties of reason and free will, the revelation of the truth whether in his works or his word, all the providential blessings and advantages which men enjoy, fall under the Pelagian idea of grace. Augustine says, Pelagius represented grace to be the natural endowments of men, which inasmuch as they are the gift of God are grace. “Ille (Pelagius) Dei gratiam non appellat nisi naturam, qua libero arbitrio conditi sumus.” And Julian, he says, includes under the term all the gifts of God. “Ipsi gratiæ, beneficiorum quæ nobis præstare non desinit, augmenta reputamus.”

8. As infants are destitute of moral character, baptism in their case cannot either symbolize or effect the remission of sin. It is, according to Pelagius, only a sign of their consecration to God. He believed that none but the baptized were at death admitted into the kingdom of heaven, in the Christian sense of that term, but held that unbaptized infants were nevertheless partakers of eternal life. By that term was meant what was afterwards called by the schoolmen, limbus infantum. This was described as that μέσος τόπος κολάσεως καὶ παραδείσου, εἰς ὃν καὶ τὰ ἀβάπτιστα βρέφη μετατιθέμενα ζῇν μακαρίως. Pelagius and his doctrines were condemned by a council at Carthage, A.D. 412. He was exonerated at the Synods of Jerusalem and Diospolis, in 415; but condemned a second time in a synod of sixty bishops at Carthage in 416. Zosimus, bishop of Rome, at first sided with the Pelagians and censured the action of the African bishops; but when their decision was confirmed by the general council of Carthage in 418, at which two hundred bishops were present, he joined in the condemnation and declared Pelagius and his friends excommunicated. In 431 the Eastern Church joined in this condemnation of the Pelagians, in the General Synod held at Ephesus.

Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, vol. 2 (Oak Harbor, WA: Logos Research Systems, Inc., 1997), 152–155.

|

| Pelagius lived from 354-418 A.D |

Note in paragraph 8 how at the time of Pelagius' life his teaching and interpretation were condemned jointly by the church in the west and the church in the east. The church in the west and east had no political love lost between them (complicated history both in terms of beliefs regarding theology, and regarding political affiliations). Despite their differences, both west and east were united in condemning the teachings of Pelagius that was contrary to the truth of scripture.

So if Pelagius got it wrong, what does scripture have to say about human abilities, choices, will, and the relationship of humanity to Good?

More on that from Hodge tomorrow...

Comments

Post a Comment