Interpreting Revelation - Four Views: Idealist

This week we've been learning and discussing the four major interpretive approaches to the book of Revelation. We've already talked about the futurist and preterist approaches, and today we'll introduce the idealist perspective.

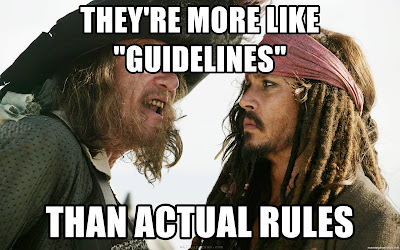

While the futurist perspective sees most of Revelation still yet in OUR future, and the preterist perspective sees most of Revelation in the PAST, the Idealist approach avoids any particular ties to specific events in the past, present, or future. If I was to suggest a meme to summarize the Idealist approach to Revelation, it would have to be from Pirates of the Caribbean since the Idealist interpretive framework looks for the grand lessons of Revelation rather than getting caught up in all the details. In this way the Idealist interpreter sees historical events (and future events) more like guidelines for interpretation rather than rules for interpreting Revelation.

The Idealist approach to Revelation

This approach to interpreting Revelation has gone through many variations of names. Some have called it the "spiritual" or "allegorical" interpretive approach. Others have called it the poetic, non-literal, or symbolic approach. This approach tends to take the various scenes within Revelation and apply them as timeless truths of application for the Christian life.

Rather than arguing for original meaning in the destruction of the temple (like a preterist) or in the future glorious reign of Jesus (like a futurist), the Idealist approach argues that the principles and lessons of Revelation are mostly ethical, moral, and spiritual, rather than historical. Steve Gregg quotes William Milligan's summary of the idealist approach to Revelation:

While the Apocalypse thus embraces the whole period of the Christian dispensation, it sets before us within this period the action of great principles and not special incidents.

Steve Gregg, Revelation, Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (Nashville, TN: T. Nelson Publishers, 1997), 44.

It is these great principles that idealist interpreters focus upon. In this interpretative framework instead of beasts, cities, empires, and timelines, the focus is put on the ultimate triumph of good over evil. Justice prevailing in the final balance. While evil seems to run rampaging over the righteous chosen of God, patience and faith are a call to arms, while courage and perseverance serve as moral guides. Daily spiritual warfare is the emphasis of Revelation according to many within this interpretive approach.

When it comes to preaching and teaching Revelation this view often comes to the forefront. Whether intentionally or unintentionally preachers and teachers can avoid "getting lost in the weeds" by simply pulling from each dramatic scene principles for Christian living. While other interpretive approaches to Revelation seek to know the details of the seven lamp stands, the plagues sent out, and the timing of the great white throne judgement, idealist interpreters are happy to make theologically applicable connections the priority.

This view out of all four seems to be the most ready made for daily devotional application. Idealist's argue that when you and I wake up for another day, does the destruction of the temple (either in the past or the future) matter for how we treat our neighbors? Is the literal or figurative beast something we need to consider when we are engaged in conflict at work, or in society? Does the past or present compare to the ethic that we are to take up our cross and follow Jesus? Thus the idealist approach may sometimes sound as though it is dismissing some of the other interpretive approaches in a more noble effort to seek God's truth.

Mutually Exclusive?

George Eldon Ladd—who is largely a futurist—concludes that “the correct method of interpreting the Revelation is the blending of the preterist and the futurist methods.” However, he also says “The beast is both Rome and the eschatological antichrist—and, we might add, any demonic power which the church must face in her entire history” (emphasis mine). Thus he combines not only the preterist and futurist approaches, but the spiritual/idealist as well.This is also Mounce’s approach. Like Ladd, he is largely a futurist in his treatment of the major prophecies of Revelation, but we find idealism combined with preterism and futurism in his view of the beast: “In John’s vision the beast is the Roman Empire [preterism] … Yet the Beast is more than the Roman Empire. In a larger sense, it is the spirit of godless totalitarianism that has energized every authoritarian system devised by man throughout history [idealism.] At the end of time, the Beast will appear in its most malicious form. It will be the ultimate expression of deified secular authority [futurism.”]Steve Gregg, Revelation, Four Views: A Parallel Commentary (Nashville, TN: T. Nelson Publishers, 1997), 45–46.

A few thoughts about the idealist perspective

- This interpretative framework is encouraging and helpful to me. But are there any grounds for asserting that this is originally what Jesus was intending by revealing this vision and commissioning John to record what he saw and heard?

- How does this particular idealist interpretation of this chapter (or passage) of Revelation differ from other possible idealist interpretations?

- Since so many Old Testament prophetical books (like Daniel, Isaiah, Jeremiah, etc) were filled with lessons with historical fulfillment in mind (like the virgin birth, the fall of Judah in 586 BC, etc) why would Revelation be devoid of historical fulfilment either in the past, present, or future?

Comments

Post a Comment